Owning a Unitron Model 160 Photo-Equatorial refractor was a dream of mine since I was about 13 years-old. Of course the price of this 4″ refractor with its attending bells and whistles was, forgive the pun, astronomical! My dream, however, was finally realized 27-years later in 1980 when I travelled by train to the Unitron warehouse in Plainview, N.Y. It was there that I purchased and took possession of perhaps one of the most elegant, and impressive astronomical instruments for an amateur astronomer that money could buy.

Two unique accessories included with the Unitron model 160 was its solid brass and chromium plated, weight driven clock drive; and the most arcane piece of photographic equipment an amateur would ever see – an astrocamera that uses glass plates! Unitron’s model 220 astrocamera was a style of camera that originally called for chemically treated 3-1/4″ x 4-1/4″ glass plates instead of standard sheet or roll film. Unitron sold these as standard equipment to amateur astronomers with their models 145 3″ and 160 4″ Photo-Equatorial refractors.

What was Unitron thinking?

Even commercial photographers of the 1950’s, when these Photo-Equatorials made their debut, would have considered these cameras museum pieces. Only a few professional astronomers might still have had a brush with such an arcane piece of equipment as a glass plate camera. Thomas Edison began using motion picture film in a 35mm format in 1902. It woud become the international standard for motion pictures as early as 1909, and 1913 for still cameras. George Eastman was the first to supply 35mm format in America.

Unitron’s glass plate astrocamera.

Glass plate negatives were coated with a hardening gelatin containing fine particles of silver salts. This was called an emulsion. These “dry plates” were far easier to work with, store and create than the difficult and dangerous “wet plate” collodian solution process which had to be used before they dried out. Dry plates, on the other hand, could be stored indefinitely. Imagine Matthew Brady working in a covered wagon on a Civil War battlefield creating wet plates all the while breathing dangerous collodian fumes! To him the dry-plate would have been the acme of photography.

Surprisingly, astronomy was the last hold-out for glass dry-plate photography. Glass plates for general photography faded out in the early 20th century. Can you say George Eastman and Kodak? But even as late as the 1950s, the first Mount Palomar Sky Survey (POSS) used glass plates, as did the follow up Sky Survey II in the 1990s.

Using the 220 astrocamera.

The Unitron 220 astrocamera came with an adapter tube which screwed to the front of the camera for prime focus photography where wide fields were desirable. A special focal length .965″ eyepiece (supplied) could be inserted into this adapter for high power lunar or planetary work. The adapter tube was then mounted and clamped to the telescope’s focusing tube.

The camera’s curtain type shutter would then be opened, and the astronomer would bring to focus the image appearing on the camera’s rear mounted frosted glass focusing screen. Once a sharp image was attained, the telescope’s focuser would be locked down to prevent movement. The shutter was closed, then set for a preset time or bulb exposure. The rear door of the camera (which holds the focusing screen) was opened and a twin-plate holder would be inserted in its place. A slide was then pulled to expose the prepared glass plate to the camera’s dark interior. After a few final checks the camera squeeze bulb was used to trip the shutter curtain at a preset speed, or manually opened and closed for any length of time from seconds to minutes.

The plate slide was then closed and the twin-plate holder was removed and flipped to bring the second glass plate into action for the a second astrophoto.The exposed plate holders would later be opened and the glass plates developed in a dark room after the observing session.

I did actually use this camera on a few occasions just to see the result. I acquired 3-1/4 x 4-1/4 sheet film adapters and cut 3 x 5 film used in my old Bush Press Camera. Using a 3-1/4 x 4-1/4 negative for lunar photography was quite impressive compared to the standard tiny 35mm format. It also had great possibilities for photographing globular clusters and open clusters. The generous spacial context of the large format compared to 35mm was overwhelming. Anyone still dabbling in the ancient arts of film photography should experiment with this large format at least once to appreciate its potential. Imagine the detail revealed by blowing up a 3-1/4 x 4-1/4 negative compared to a tiny, grainy 35mm?

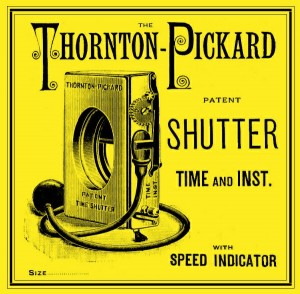

Who or What is a Thornton Pickard?

The Unitron 220 astrocamera uses a Thornton Pickard shutter that was a very common shutter mechanism used in British plate cameras of the 1880s. The shutter is actually a large curtain which could be opened indefinitely for time exposures, or controlled by preset shutter speeds to open and close. In fact, the entire wooden box of the Unitron 220 camera, with its primitive gears, “hair pin” spring and lever is an exact duplicate of the 1880 Thorton Pickard patent camera. Arcane is the perfect word indeed.

Some things do not improve with age.

Every owner of a 220 eventually discovers that its natural rubber squeeze bulb, which operated the shutter, has turned to stone. Some just lose their pliability while others liquefy leaving a terrible mess inside the 220’s cabinet. In working with my 220 for astrophotography, I discovered that the hole in the camera’s release lever was threaded to accept a modern cable release. I would recommend picking up a cable release for your 220. Even though you may never use the camera, the cable insures that it is still an operational relic. Any 145 or 160 owner will understand and appreciate its collector value.

A closing thought. Be sure to operate the shutter mechanism periodically so the curtain will not dry out, flake or fail to close properly. Good advice for ANY old camera sitting on the shelf.

Steve Franks, December 2014